By Twink Jones Gadama

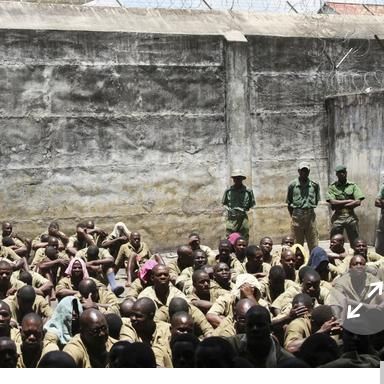

In a move that has sparked intense debate and raised concerns about human rights, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is preparing to execute over 170 inmates convicted of armed robbery. The inmates, aged between 18 and 35, were flown from the capital to a high-security prison in the north, where they will face the death penalty.

According to Congolese Minister of Justice Constant Mutamba, 70 of the convicts were transported on Sunday, joining 102 other prisoners who had already been sent to Angenga prison in the northern Mongala province. The inmates are locally known as “Kulunas” or “urban bandits,” and their convictions have been met with a mix of relief and concern from the public.

While some have welcomed the measure as a means of restoring order and security in the cities, others have expressed concerns about the risks of abuse and human rights violations. Fiston Kakule, a resident of the eastern city of Goma, said, “We welcome this decision by the minister because it will help put an end to urban crime. From 8 p.m. onwards, you can’t move around freely because you’re afraid of running into a Kuluna”.

However, human rights activists have warned of the possibility of extrajudicial executions and called for a strict respect for judicial procedures and fundamental guarantees. Espoir Muhinuka, a human rights activist, said, “The situation in the DRC is complex and requires a multidimensional approach. The fight against urban gangs must go hand in hand with efforts to combat poverty, unemployment, and social exclusion, which are often contributing factors to crime”.

The use of capital punishment in the DRC has been a contentious issue. The country abolished the death sentence in 1981 but reinstated it in 2006. The last execution took place in 2003, and there have been no reported executions since then. However, in March 2024, the Congolese government announced the resumption of capital punishment in cases of treason by military personnel.

The decision to execute the inmates has raised concerns about the potential for abuse and miscarriages of justice. Muhinuka warned that political pressure could lead to unjust convictions and arbitrary executions. “The situation in the DRC is complex, and we need to ensure that justice is served in a fair and transparent manner,” he said.

As the executions loom, the international community is watching with bated breath. The use of capital punishment is a highly contentious issue, and many countries have abolished it altogether. The DRC’s decision to resume executions has sparked concerns about the country’s commitment to human rights and the rule of law.

In the midst of this controversy, the stories of the inmates and their families have been lost. Many of the inmates are young men who were convicted of armed robbery, often in desperate circumstances. Their families are left to pick up the pieces, wondering what could have been done to prevent their loved ones from turning to crime.

As the DRC prepares to carry out the executions, it is essential to remember the human cost of this decision. The inmates may have committed crimes, but they are still human beings, deserving of dignity and respect. The international community must continue to pressure the DRC to respect human rights and the rule of law, even in the face of overwhelming public pressure to execute the inmates.

In the end, the decision to execute the inmates is a complex one, fraught with controversy and concern. As the world watches, it is essential to remember the human stories behind the headlines and to continue to advocate for human rights and the rule of law.